Imagine a quiet farm beneath a full moon. The cornstalks whisper. In the center of a field stands a scarecrow, constructed from straw, sacks, and a threadbare jacket.

At first it appears ordinary. Then it moves, slow and deliberate. Its burlap face contorts into a silent scream.

This figure is Harold, simple in form yet devastating in effect, and one of the most memorable characters in Harold Scary Stories to Tell in The Dark.

Harold’s potency is deceptively straightforward. A single, arresting image—an object designed to frighten birds—turns against the humans who created it.

This reversal evokes anxieties that predate literacy and encapsulates a moral lesson that young readers comprehend intuitively.

Over successive decades, Harold has lodged in the popular imagination through the terse, folkloric prose of Alvin Schwartz and the grotesque, unforgettable inkwork of Stephen Gammell.

This article examines Harold’s origins, narrative mechanics, variations, psychological reach, and cultural impact, and explains why the scarecrow continues to trouble readers long after its initial appearance

A Compact and Potent Premise

Effective horror frequently arises from conceptual economy. Harold exemplifies this principle. The narrative establishes a readily visualized scenario and then introduces a single, inexplicable element that destabilizes the world of the story.

The premise is so concise that it can be summarized in two sentences: two farmhands construct a scarecrow, they abuse it, it animates and enacts retribution. Despite its brevity, the story leaves a lingering impression.

This economical plot structure is linked to an ethical core, namely that cruelty produces consequences.

The internal logic of the tale is simple and thus persuasive; the outcome feels inevitable. Horror that functions as a moral fable operates on two registers, it frightens and it conveys an ethical lesson, whether explicit or implicit.

For both children and adults the coupling of action and consequence provides a satisfying, and concurrently unsettling, resolution. An apparently thoughtless act may invite an unforeseen response from the world.

Folkloric Foundations: From the Alps to the American Farm

Harold does not emerge from a cultural vacuum. Schwartz’s approach draws on oral traditions and folkloric motifs that recur across regions.

Animated scarecrows and analogous figures appear in numerous cultures because they engage with animistic assumptions, the conviction that material objects may possess agency.

The Alpine Sennentuntschi legend is frequently cited as a proximate source, in that a life-like effigy is fashioned, mistreated, and subsequently turns on its creators.

Comparable motifs exist among Japanese yokai, such as the kasa-obake, an umbrella that acquires life, and in Slavic narratives that describe household spirits which are benevolent when honored and dangerous when offended.

Schwartz possessed the sensibility of a folklorist; he recognized the nucleus of these tales and reframed them within an American rural context.

By situating Harold on a farm he localized the myth without diminishing its archetypal resonance. The barn, the cornstalks, and the solitary night function as archetypal settings for dread in American literature, so that the tale reads as simultaneously contemporary and ancient.

In this formulation the scarecrow becomes a vessel for anxieties about neglect, cruelty, and metamorphosis.

Harold Scary Stories to Tell in The Dark

Some stories are meant to be whispered… but Harold’s aren’t. Step into the shadows, if you dare, and meet the tales that creep into your mind long after the lights go out.

1. The Watching Straw

Old Miller’s field lay at the edge of town, a thin ribbon of corn between the road and the wood. The boys called it Miller’s Maze because the stalks grew tall and close enough to swallow a child.

On a bright, bored afternoon, three of them made a thing to make them laugh, a scarecrow from Miller’s thrown-out coat and the burlap bag that had been used for seed.

They propped it on a cross of wood and gave it a face with black buttons and a scribbled smile, then they named it “Mr. Grin” and dared each other to spit at it.

At first the thing did nothing. It hung limp, an awkward joke in a suit. The boys took to it every day, pelting it with mud, sticking it with corn cobs, and shouting rude things behind their hands. When night came, they would run home with their knuckles white.

On the fifth night after Mr. Grin was made, Mrs. Harlow walked out at dusk to gather eggs and saw something move near the corn’s rim. She thought at first it was a deer until she looked long enough to see the coat turn. The scarecrow had shifted its shoulders. It stood up straighter, as if testing whether its new joints worked.

People said it was the moonlight. They said it was a trick of the shadow. But Miller’s hounds began to howl at midnight in a way they never had before. Farmers swore their plows caught on something like twine.

A crow that had hunted the field for years dropped from the air one morning, its feathers ruffled as though it had been grabbed.

The boys woke one dawn to find the scarecrow missing from its post. In its place, a ring of flattened dirt lay in the center of the field as if someone had been pinned and left to dry.

No one saw the boys after the next harvest. Sometimes late at night, drivers said they saw a coat move at the corn’s edge, a hat lifted as if to look for passersby. People began to lock their doors earlier in the year. The field stayed quiet until snow.

They stopped making jokes about Mr. Grin. They stopped looking at old coats in the same way. The watching straw had taught them how easily something intended to be watched could begin to watch back.

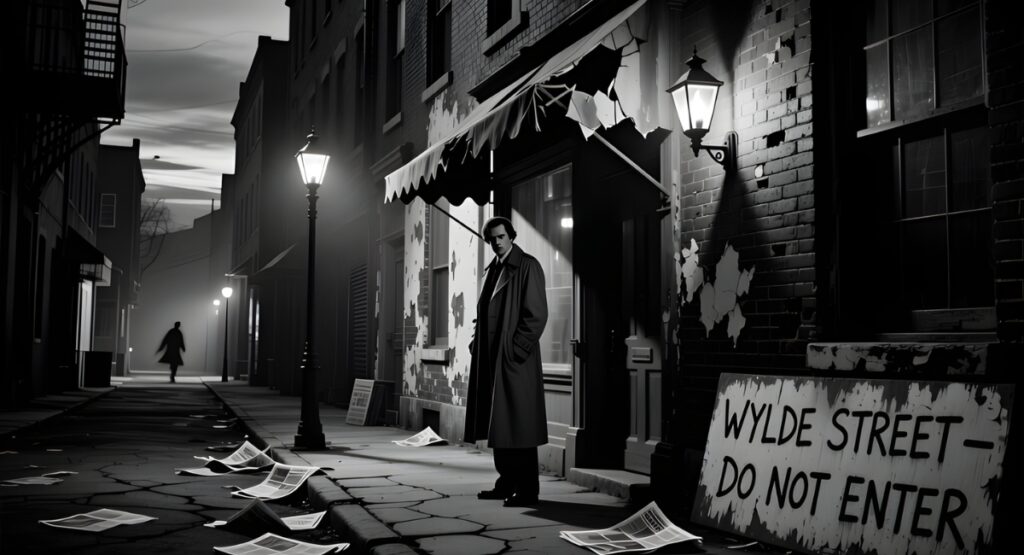

2. The Shadow Over Wylde Street

Wylde Street ran behind the old textile mill. The lot beside it had been abandoned for years, weeds and broken benches and a rusting swing.

Teenagers met there to drink and throw stones through the boarded windows of the mill. One summer they found a pile of sacks, a head of straw someone had left, and they laughed and stuffed the sacks into a wooden frame.

They made the face coarse and mean. They named it after a teacher they disliked, a small act of cruel ventriloquism.

At night, the lot felt watched. Things that walked by heard a soft, dragging sound that they could not place. Some said it was rats.

Others said it was just wind. But one boy, Tyler, who had mocked the teacher more loudly than the rest, found his backyard light extinguished one dawn, and a dark smear lay across his lawn like someone had dragged a blanket and then erased it.

The thing in the lot did not move like a person. It moved like an absence, a patch in which light was thinner.

When it came close to people who had been cruel, the air dropped in temperature, and their breath fogged even in summer.

Small pets refused to go near windows where the shutouts could be seen, and mothers began to call their kids home early.

One night the teens dared Tyler to steal back the sacks and burn the face. He ran with a lighter and a bottle, heart pounding, and just at the edge of the lot the darkness reached for him.

He swore it pulled at his shoes as if to pin him to the ground. He dropped the bottle and fled, the smell of straw and something burnt chasing him more surely than any dog.

Tyler left town soon after. People said the lot was emptier where the shadows pooled, as though a mark had been left on the place.

The kids stopped giving names that could be worn like insults. Their voices grew quieter on the street. They learned there are corners of the world where shame can sleep and wake watching.

3. Night Shift at Hollow Farm

Hollow Farm had been in the Weaver family for generations. It fed a town of a few hundred people and had a scarecrow, sewn from old overalls and the wedding shawl of Mrs. Weaver’s grandmother.

The scarecrow’s name, given by the youngest Weaver, was “Biddy.” No one thought much of it. It stayed on its post and looked over the field like a dull-eyed steward.

Late on a September night, two men from the city came through, laughing and throwaway air about town life.

They trudged the rows crushing small green shoots for sport, mocking the old rules and spitting near the scarecrow’s post.

The next day, the town found prints in the earth that were too long, as if someone with wickedly wide feet had paced the soil. The weeds along the fence had been nicked neatly, a pattern like stitches.

That night, while the men slept in their rented room, something tapped lightly at the windowpane.

One woke and looked to the fields. Under moonlight a figure was walking through the rows, its arms long and stiff, its head cocked like it listened for voices.

The next morning, the two men were gone. Their truck was at the side of the road, keys still in the ignition, sandwiches left on the seat.

No sign of them was ever found, but the next harvest, Mrs. Weaver noticed small bundles of straw tied and placed at the edge of the town’s common, as if the land itself had set a tidy warning.

People no longer walked that strip alone at night. The factory that had once employed those men had a new whisper: pay attention to where you tread.

Hollow Farm’s old scarecrow had kept its vigil. It had taught town newcomers that the fields remembered who had walked on them without care.

4. The Harvest Reckoning

There was a village that kept a long row of market gardens, every plot tended by hands that had learned the rhythm of soil and season.

A family from the next district came for the festival and trampled a child’s sunflowers in a drunken game. Laughter followed. The sunflowers did not stand again.

At dusk the scarecrow at the center of the communal garden, a figure the villagers called “Keeper,” seemed to lean closer to the path. No one thought it could move. Keeper was old, a coat sewn with mismatched buttons and a straw hat threaded with daisies.

The next morning, the family that had trampled the flowers woke to find their front yard strewn with tiny, neat rows of seeds, pressed into the ground in patterns that looked like footsteps.

Their dog would not enter the yard. Their youngest boy woke in the night and said he had seen a tall man in a coat place the seeds, his hands smelling of earth.

The family stayed up for nights, watching the road. They began to weed the garden next door in secret. Slowly, with awkward and halting care, they learned the names of plants that kept to their climate.

They planted a patch of seedlings of their own and watched them with small, new gentleness.

At the next festival, they brought a basket of produce they had grown, and they left a small token on Keeper’s post, a ribbon, not in fear but as thanks.

In that village people told the old tale to children who stomped in the seed beds. They told it to remind each other that land remembers rough hands and answers, sometimes in ways that teach instead of destroy.

Keeper’s harvest reckoning was less vengeance and more a slow lesson, one that turned shame into the careful work of repair.

5. Harold Speaks, If You Dare to Listen

I was stuffed by hands that thought themselves clever. They chose a name that sounded small, harmless, as if a label might keep me ordinary.

They laughed when they saw the stitches. They thought I would be a thing that would keep birds away and nothing more.

At first I only smelled of the people who made me, and the heat in their fingers when they tied my hat. Their voices were a low hum above the field and the corn listened to every word.

They called me jokes into being, easy targets for their boredom. I listened for what they wanted me to be and I learned their language, bone by bone.

The bruises they left on me were not like wounds, they were ideas pressed deep into straw and cloth. Each sneer taught me how smallness tasted.

Night taught me other things. Moonlight showed me how the world breathed. Wind taught me how to stretch and fold, how the empty places inside me could shift.

The field remembers motion. The field remembers who walked on it like a promise. Their cruelty was a note too loud in the land’s hearing; the soil answered in the long, slow way soil always answers.

When I moved I tried first to be the thing I was made to be, a line on the horizon, a shape for birds to avoid. But the shape some days wanted to stand. I would test a wrist, an arm, the looseness of my coat.

I would listen for the name that had been given to me and watch how the named thing fits in the world. Names wear people like clothing. Give cruelty a name and it keeps its shape.

Now when someone comes with hands that think themselves clever I look at them and I remember the sound of their laughter.

I think of what it is to be woven, and I think of the quiet work of undoing hard things. I do not speak with words. I move. Sometimes it is enough.

The Canonical Tale: From Mockery to Retribution

The canonical account centers on two farmhands, Thomas and Alfred, who are bored and cruel. They construct a scarecrow and assign it the name Harold, itself an act of derision aimed at a disliked neighbor.

They proceed to taunt and mistreat the effigy. Initially, peripheral noises around the scarecrow are attributed to nocturnal animals or the mind’s imaginings.

The scarecrow’s behavior, however, escalates: it stiffens, moves, climbs, and at the narrative’s climax becomes an instrument of horrifying retribution.

One of the men disappears, and the image that confirms the horror is that of human skin stretched and left to dry.

The narrative architecture is spare and exact: exposition, escalation, grotesque disclosure. Schwartz’s prose, characterized by brevity and directness, amplifies the dread; the short, staccato sentences compel readers to supply sensory and emotional detail.

The effect is not one of rhetorical excess; rather it is a precisely calibrated mechanism that produces sustained unease.

The Visual Aspect: Stephen Gammell’s Distorting Imagery

Schwartz’s text supplies the structural framework of the tale, while Stephen Gammell’s illustrations supply its affective force.

Gammell’s technique, composed of skeletal linework, ink smears, and liquefied facial features, performs a rare function: the art refracts and extends the text, altering how each line is perceived.

In Gammell’s renderings the scarecrow appears as a creature suspended between states, part straw and part anatomical suggestion, with motion implied by ink strokes that trail beyond the page. The images do not comfort; they intensify uncertainty.

A reader who encounters Gammell’s blurred, distorted Harold is likely to supply the remainder of the horror from imagination, and that act of supplementation often results in a greater dread than any literal depiction could achieve.

Illustrations typically constrain imagination; Gammell’s work does the opposite. For many readers the image becomes the primary memory of the encounter, superseding the text.

The synergy between minimal prose and maximalist, nightmarish art is central to Harold’s enduring power.

Variants, Adaptations, and Derivative Forms

The central motif, an abused object exacting revenge, is adaptable, and iterations of the Harold archetype appear in multiple contexts.

Harold as Shadow

Some retellings render Harold less corporeal and more atmospheric, a shadow or presence that haunts those who have committed cruelty.

This psychogenic variant uses implication rather than depiction, and the unseen presence often proves more disturbing than a visible antagonist.

Harold in Urban Contexts

Urban reinterpretations transpose the scarecrow into vacant lots, playgrounds, or abandoned industrial sites.

In these versions Harold punishes bullies and vandals. The motif thereby migrates from rural moral instruction to commentary on urban social disorder.

Harold and the Harvest

Certain adaptations emphasize Harold’s connection to the land. In these narratives Harold responds to desecration of crops and gardens, transforming the figure into an ecological agent that enforces respect for the soil.

Cinematic Harold

Guillermo del Toro’s 2019 film adaptation of Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark reimagines Harold for the screen, employing movement, sound design, and prosthetic effects to render the scarecrow corporeal and kinetically frightening.

The cinematic Harold preserves the moral axis—that cruelty is answered—while translating the archetype into visual and auditory languages suited to contemporary audiences.

Each iteration preserves the narrative’s nucleus, that cruelty yields consequence, while altering particulars to accommodate changing contexts, periods, or media. The motif’s adaptability contributes substantially to its longevity.

Explanatory Frameworks: Psychological and Literary Foundations

Harold’s persistence may be attributed to several convergent mechanisms.

The Uncanny

Harold occupies a liminal zone between animate and inanimate. This liminality produces an uncanny effect; cognitive expectation is violated and fear ensues.

When an object typically understood as lifeless exhibits agency, the resulting cognitive dissonance registers as threat.

Economy of Suggestion

Schwartz’s spare diction privileges suggestion over exhaustive description. Readers participate in meaning making by furnishing omitted sensory detail, and such participation frequently amplifies terror.

Moral Satisfaction

Horror that enforces a form of retributive justice offers readers a sense of karmic equilibrium. Confronting fear while observing an ethical balance provides an emotionally coherent experience.

Isolation as Intensifier

The settings, often lonely farms or abandoned lots, generate vulnerability and thereby heighten suspense. Absence of institutional recourse renders consequences absolute within the narrative world.

Illustrative Synergy

Gammell’s imagery consolidates the tale within visual memory. When text and image mutually reinforce each other, the resulting iconography becomes portable and persistent.

These mechanisms operate in combination to produce Harold’s cultural durability.

Thematic Complexity Beyond Immediate Shock

Harold is not merely a vehicle for fright; the tale articulates multiple thematic registers.

Cruelty and Retribution

The most immediate theme concerns the reciprocity of harm. The scarecrow functions as a mirror, reflecting the moral failure of those who commit cruelty.

Neglect and Animacy

The notion that neglect engenders agency functions as an ethical admonition. Objects treated harshly may, within the tale, acquire a capacity to respond.

Othering and Projection

Assigning the name Harold to the effigy, often derived from a disliked neighbor, constitutes a form of dehumanizing projection. The narrative implicates social practices of scapegoating by demonstrating how animus directed outward can rebound inward.

Fear of the Rural Unknown

The scarecrow resonates as an emblem of rural dread, channeling anxieties about spaces located beyond communal surveillance.

Extra-legal Social Regulation

In settings where formal authority is remote, folkloric narratives perform regulatory functions. Harold operates as a form of social enforcement in locales where institutional justice is absent or ineffective.

These thematic layers enable the tale to function as moral fable, psychological study, and cultural commentary.

Pedagogical and Domestic Applications

When introduced with appropriate sensitivity, Harold’s narrative can serve as a productive pedagogical resource for teachers and parents.

For Younger Audiences

Provide an explicit content warning. Use an abridged retelling that emphasizes mood rather than graphic detail.

Employ art activities in which children construct scarecrows while discussing care and respect, thereby transforming fear into an exercise in empathy.

For Middle-Grade and Adolescent Readers

Situate the tale within a folklore unit, drawing comparisons with Sennentuntschi, kasa-obake, and other animate-object narratives.

Facilitate ethics discussions that present competing perspectives on justice. Use creative writing prompts that invite students to retell the story from alternative vantage points, such as the effigy’s perspective.

Employ visual analysis exercises to examine how line, contrast, and texture generate affect.

For Secondary and Tertiary Education

Adopt psychoanalytic frameworks to explore projection and scapegoating, and arrange adaptation projects that require students to convert the tale into screenplay form, with attention to sound design and pacing.

These applications enable educators to transform the tale from a simple scare into a catalyst for critical thinking and aesthetic inquiry.

Controversy, Censorship, and Cultural Reception

The Schwartz-Gammell volumes faced recurrent challenges on account of their unsettling illustrations.

The resulting controversies illuminate a broader cultural ambivalence about children’s exposure to fear.

Protective impulses to shield minors from disturbing imagery frequently conflict with the pedagogical value of permitting children to experience calibrated fear.

Attempts to ban the books sometimes intensified their appeal, rendering them objects of forbidden desire and thereby contributing to their folkloric aura.

These debates supply fertile material for classroom discussion about censorship, artistic expression, and media literacy.

Cultural Dissemination and Influence

Harold’s influence extends beyond direct retellings. The scarecrow motif recurs in filmic, televisual, and digital culture as shorthand for rural menace, moral inversion, and uncanny retribution.

Filmmakers, authors, and visual artists employ the archetype when they require a compact symbol of inarticulate but inexorable judgment.

The migration of the motif from a single narrative into a larger symbolic vocabulary indicates the tale’s cultural resonance.

A Close Reading: Syntax, Rhythm, and the Construction of Suspense

A brief technical analysis clarifies how Schwartz constructs dread at the sentence level.

Concise Sentences

He uses short, declarative sentences that interrupt narrative momentum at disquieting junctures.

Repetition and Incremental Escalation

Small, recurring details, such as a noise or a twitch, reappear with increased intensity, a canonical suspense technique.

Omission and Suggestion

Strategic elision of explicit sensory detail—particularly regarding the climactic act—compels readers to imagine the worst.

Rhythmic Modulation

The prose rhythm accelerates as the narrative progresses, mirroring escalating tension and anxiety.

These devices together generate a sense of inevitability, propelling the reader toward the story’s consummation.

Prospective Adaptations and Analytical Angles

Writers and filmmakers may consider several approaches when adapting or reinterpreting the Harold motif.

Empathic Harold

Narrate from the scarecrow’s perspective and probe the motives that drive its actions, whether pain, preservation, or a residual force of land and memory.

Urban Folktale

Relocate the archetype to contemporary urban settings in which social media amplifies cruelty and in which collective shame or vigilantism may arise.

Ecological Parable

Emphasize the landscape as an agent, and interpret Harold as an enforcer that responds not only to personal cruelty but to environmental degradation.

Moral Ambiguity

Present the scarecrow’s actions in ethically ambiguous terms, prompting readers to interrogate the nature of justice in contexts where formal systems fail.

These vectors demonstrate the motif’s conceptual flexibility.

Content Sensitivity and Ethical Guidance

The tale functions by engaging primary fears, and sensitivity is requisite. Because the narrative invokes graphic imagery and themes of retributive violence, educators and caregivers should assess developmental appropriateness. For vulnerable readers, emphasize atmosphere and suggestion rather than explicit description, and provide debriefing prompts to facilitate emotional processing.

The Enduring Significance of Harold

Narratives survive insofar as they address persistent human concerns in forms amenable to retelling.

Harold articulates anxieties about accountability, the consequences of neglect, and the manner in which material objects retain traces of human conduct. The scarecrow serves as a compact metaphor for these concerns.

Moreover, the conjunction of terse, folkloric prose and liminal, grotesque imagery produces a cultural shorthand: one succinct visual—a burlap face, hollow eyes, elongated limbs—evokes a fully realized narrative and the affective trajectory it entails.

That shorthand is portable; it travels readily across retellings, media, and cultural boundaries. Harold’s image is sufficiently simple to reproduce and sufficiently complex to sustain fear. That equilibrium of simplicity and depth renders Harold a durable figure in children’s horror.

Conclusion

Harold retains his capacity to frighten because his concept is precise and concentrated. He channels ancient warnings through a modern narrative mechanism: cruelty produces consequences, and neglect is not inert.

The figure operates as an archetype of the uncanny and as a moral fulcrum, demonstrating how image and text may collaborate to imprint dread upon memory.

In a field beneath a full moon the cornstalks continue to whisper, and somewhere a scarecrow still listens.